The book Marine: The Life of Chesty Puller, tells the story of the most decorated Marine in American history. Chesty Puller.

Book By Burke Davis. Book study for F3 Suncoast. Below, is a short excerpt from the 1962 book, and study questions. Copies of the 1991 Bantam paperback are available at our Wednesday meetup.

Discussion Questions

- Lewis Puller did not have to go to Haiti, when then, as now, is filled with violence and corruption. Does our choice to enter a hard situation make these compromises expected?

- He chose to go as a 20 year old, not expecting what he found. He ended up losing a friend. How does age affect these decisions?

- In a hellish situation, do the rules change for us if we are trying to lead others to safety?

- Confronting evil is never easy. How do we stop it without becoming it?

- It is easy to be moral when you are in a place of comfort, as we are today. How do we lead in such a situation when we are confronting our mere existence?

Practical Leadership Questions

- Rules and Rule-breaking: In instance after instance, Puller did not follow the rules or expecations, including asking for intravenous quinine for his malaria. Was he just lucky, or is there something to be said for operating outside the rules?

- The Acceptance of Horror: Puller’s loss of his friend, Muth, in battle, and the subsequent mention of Haitians eating his heart is only a short mention.

- The Use of Words: Someone killed a man for a horse that Puller admired. He learned the lesson to guard his comments as a leader. When have you realized you need to be careful what you say if you are in a leadership position in family, business or sport?

- Paths to a Goal: Puller took an unorthodox path to an enlisted commission. How can we find alternate ways to reach the goals we set.

Book Intro

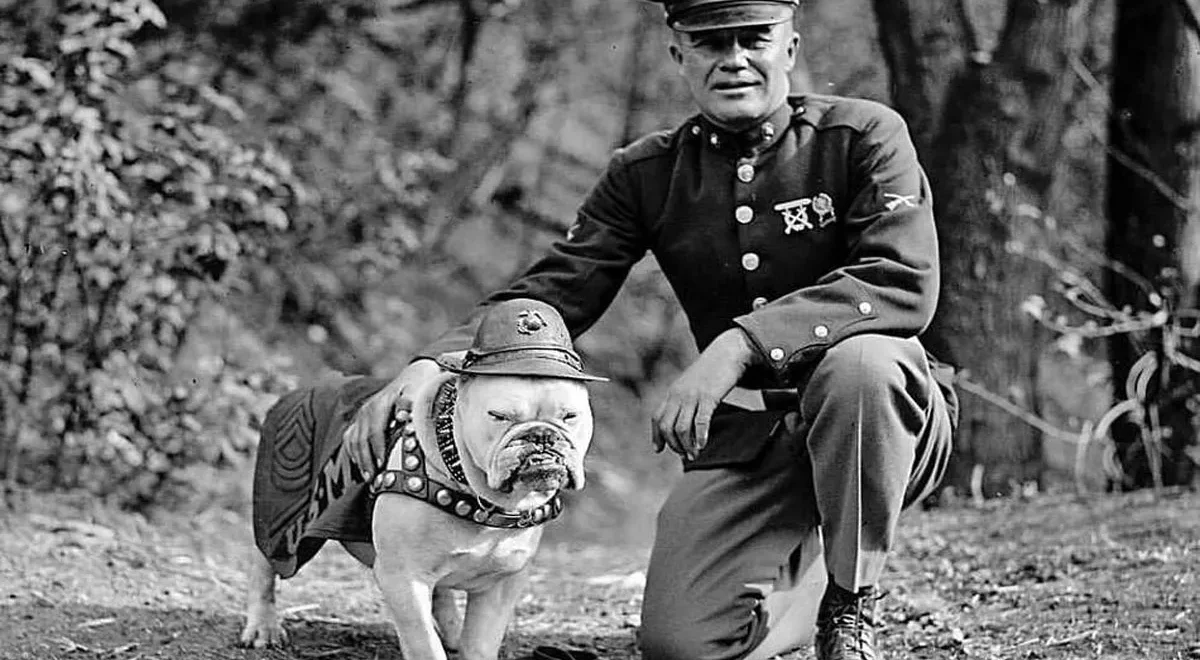

Lewis Puller was one of the rarest of Marines, a onetime private who rose to become a lieutenant general. From a boyhood haunted by tales of his Confederate ancestors, his life had been one long preparation for war. He had lived through more than a hundred combats in the banana wars of Haiti and Nicaragua to win a grim nickname: El Tigre. He had been accused of paying bounty for the ears of native bandits.

He had commanded Horse Marines in Peking in the early ’thirties, and in Shanghai, on the eve of World War II, he had driven a superior force of Japanese troops from the American quarter at gun-point. He had been trained for battle as an infantryman, cavalryman, artilleryman, aviator and shipboard officer. He had led the first championship Marine drill team and had been famous as student and instructor in military schools.

In the first Allied offensive of World War II, at Guadalcanal, he had with one half-strength battalion saved Henderson Field by standing off a Japanese division. On that island his men had won two Medals of Honor, twenty-eight Navy Crosses and Silver Stars—and two hundred sixty-four Purple Hearts.

His career began when he and friend Lawrence R. Muth, at age 20, decided to enlist in the Polish army. On a visit to Washington, a Marine Captain told them that if they wanted to join the Marines, the best fighting was in Haiti, not Poland. He told them that “They need men, and there’s plenty of fighting. You’d see action and have some fun.

So they signed up for the Gendarmerie d’Haiti.

Reading for Wednesday, May 4, 2022

Chapter III: Baptism of Blood

The stench of the tropics welcomed the young Marines to Port-au-Prince when the ship entered the harbor, a sour-sweet breath from mountain forests which also bore the taint of decay from the waterfront. Beyond the red-roofed city the hills rose incredibly green. It was mid-July, 1919.

Puller and Muth got a brisk greeting from Captain Donald Kelly at the barracks: “Report at 4:30 in the morning, equipped for battalion drill. You might like a few beers in the hotel, but beware that rum.”

Haiti was the strife-torn western tip of the island shared with the Dominican Republic; revolutions had been shaking the government since 1914, after almost a century of freedom from France. Since 1916, at the request of the Haitian government, Marines had policed the country amid violence which had taken nearly 2000 lives, almost all Haitian.

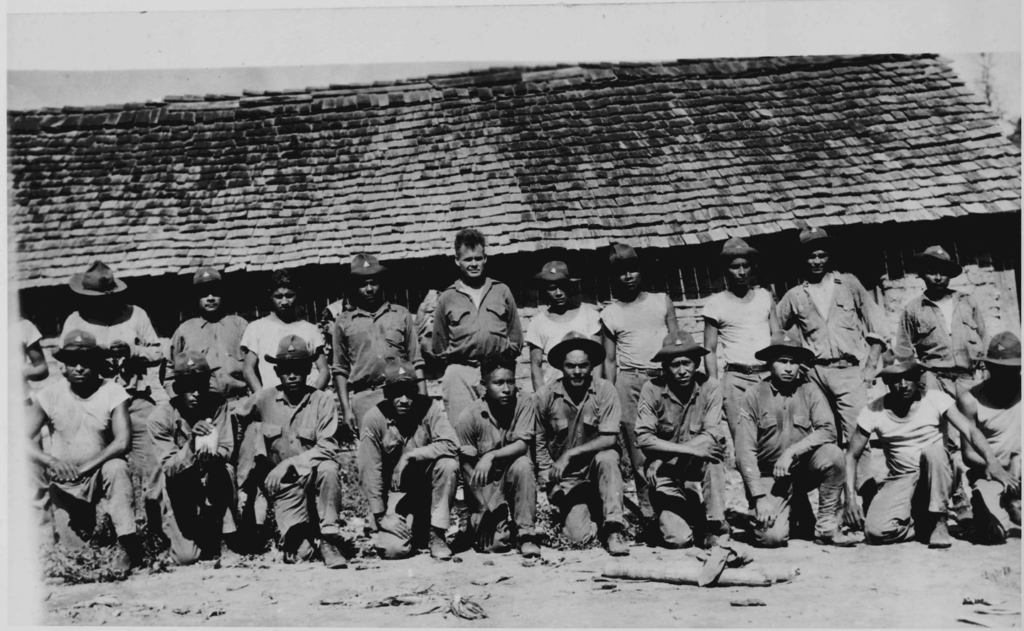

General Smedley Butler had created the Gendarmerie d’Haiti with a shrewd disregard for precedent. The senior officers were U. S. Marine officers, whose brief tours of two years created a supply of field-trained commanders. But he chose Marine enlisted men to act as junior officers of his constabulary and allowed them to stay as long as they wished, on the theory that they became more valuable as they learned the language and customs of the people. In practice it was these Marine enlisted men who operated the force.

In 1919 the rebels were the Cacos, fierce jungle-wise tribesmen who roamed the hill country, pillaging settlements and sometimes sweeping into the cities; even the capital, Port-au-Prince, was not safe from their raids. Atrocities were common. The war was five years old when Lewis Puller arrived for his first taste of combat, and it still raged furiously.

Puller and Muth were roused by a Haitian maid at 3:30 the next morning with a pot of alarmingly black coffee, a French roll and a jigger of rum. At sunrise they reported for battalion drill. As he fell in Lewis saw a striking soldier: Sergeant Major Napoleon Lyautey, a quadroon who stood well over six feet, a lean, powerful figure of about 190 pounds, a man of remarkable poise. His high, thin nose gave him an aristocratic expression; his pale brown scalp was as bald as an egg.

Around the barracks a line of Haitian women squatted against a wall. When the battalion was dismissed every native soldier stripped naked and the women charged into the open, surrounding them. They brought changes of clothing for the troops and bundled up the sodden garments the men dropped to the ground. While the change was made the women laughed, watching their men and merrily pointing out the variety of exposed charms. They soon disappeared with the soiled clothing. Puller thought it the most efficient laundry service ever devised.

His first foray into enemy country came without warning. The following night at dinner Captain Kelly gave him a casual order:

“A noncom will pick you up at 3:00 A.M. tomorrow on horseback. You will take a pack train to Mirebalais and Los Cohobos. You will carry ammunition and shoes, with an escort of twenty-five mounted men and a sergeant.”

Before he went to bed Puller consulted older officers as to the location of the inland towns. When he faced his men in the morning he found that none spoke English.

The first stop was Mirebalais, a town forty miles away, by roads through bandit-infested country. Puller determined that he would not spend the night in the open, for his head was full of tales of ambush in the Philippine campaigns. While they were hurrying along the trail his sergeant often came to him to complain, gesturing wildly, but Puller could not understand him.

About 4:00 P.M., without warning, Lewis stumbled into the first fight of his career—and proved his instinct for combat. The pack train was ambling around a wooded bend between hills which were littered with stones and cactus, when it met an oncoming Caco band of about a hundred, equally surprised, and in the same formation. Puller spurred his horse and yelled: “Charge! Attack! Vite! (Hurry!)”

The column charged, horses, pack mules and all, and in the thunder and dust and fierce yells the Cacos broke for the hills, firing a few stray rounds as they went. They were gone so quickly that Puller doubted his senses for a moment, but he had shot one of them, a small black barefoot soldier from whose body he took a sword so fine that he could touch its point to the hilt.

Puller’s only casualties were superficial bullet wounds to five of his horses and mules.

During the stop at Mirebalais, Puller saw a Haitian soldier report from a raid deep in Caco country. The soldier, Private Cermontoute, reached into his saddle bags and drew out two heads—black, grinning masks already beginning to shrink, lips drawn back over gleaming teeth. He held them high for the Marines to see, immensely proud.

Within a few days Puller was back on the trail, driving his mule train to mountain outposts.

The next morning Lewis took his company of 100 by rail to the hill town of Croix de Bouquet. His officers were the newly commissioned native lieutenants, Lyautey and Brunot, and his first sergeant was one Clairmont, a tiny black man who exercised perfect control over his troops. In the ranks was also Private Cermontoute, the head-hunter, whom Puller had pried from Weedor’s command by promising to make the young native a corporal, though he could neither read nor write.

They had only two days of training before plunging into the wild country and Puller spent much of it on the rifle range, where he saw each man fire twenty-five rounds—the first of his efforts to teach every man who served with him to become a sharpshooter. He also broke up the squads into two four-man firing teams, anticipating Marine Corps policy by twenty years.

With the aid of Lyautey and Brunot he drilled the men for short fights against the enemy in ambush. He used his bugler, who would march with him on the trail, to sound “plays,” in the manner of a football coach. One bugle blast, and the column faced left; two blasts, to the right; three blasts, and the two leading platoons deployed into line.

They marched fifty minutes of each hour, much of it at double time, and Puller soon found that he had no more need of the ten-minute rest periods than his mountain-trained soldiers.

The column soon halted and when Puller moved up he saw a camp follower giving birth to a baby. A group of women calmly attended her at the trail-side. Puller was alarmed, but Lyautey assured him: “It happens much with our people. The column may move. The women will see to her, and she will soon be marching with us.”

At reveille the next morning a proud, grinning soldier, Private François, brought his wife and a greasy baby boy to be admired. The child was covered with gun oil in the absence of other lubricants and gave off a martial aroma as he suckled. The woman walked with the column all day.

On the trail soon afterward, the Captain had a lesson in the stern discipline of the Haitian troops. A soldier near the end of the column began to straggle, a shining black man whose body shook with rolls of fat. He sat at the side of the trail moaning that he was exhausted. Lyautey barked orders and the yelping culprit was trussed with a lariat tied to the saddle of a pack mule, and was dragged at a lively pace along the trail.

The body thumped and tumbled for several hundred yards, until the screams had subsided to groans of desperation. Lyautey then relented and the bleeding man staggered to his feet. To Puller’s astonishment he straggled no more and made his way with the column until the next halt, when he fell as if he had been poleaxed.

“It seems cruel, Captain?” Lyautey asked. “Without it, the patrol must fail, for if one man falls, others will fall out. They will indulge their weakness, and we cannot allow this. Do not forget that we are fifty miles from base, Captain—and that if we had left this man alone on the trail for one hour, our tender friends the Cacos would have cut him into ribbons.”

Puller was convinced, but when he looked at the blood-crusted skin of the sleeping soldier, Lyautey smiled. “Within a week, Captain, he will be a new man. We are not so savage as we seem.”

At mid-morning, a few days later, the head of the patrol reached the banks of La Chival River, in the remote country near the San Domingan border. The men halted, under orders, until Puller came up. The river was about seventy-five yards wide. From the opposite shore a native in Domingan dress rode out on a magnificent horse, a big buckskin with white mane and tail who splashed through the shallows under perfect control, though without bridle or saddle.

“A wonderful horse,” Puller said. “I’d surely like to have him.”

Brunot muttered in Creole and a rifle cracked. Puller saw one of his men pull his rifle bolt and eject a cartridge. The beautiful horse stood in the river, looking nervously about. His rider floated downstream in a stain of blood. The stunned Puller turned to Brunot: “Did you order that man shot?”

“Hell, sir. You said you wanted the horse. Anything the Captain says is our command. We have discipline here, sir.” The men seemed unmoved by the cold-blooded killing.

“My God! Catch the horse, get the men over the river—and see if you can find that man’s family.”

Lewis never again expressed himself idly before these soldiers. His search for the family of this victim was futile, but the horse was his mount for years in Haiti, a strong young stallion which never failed him.

During the rest on a ridge a man handed Puller half a pineapple. Lewis began to eat it, but tossed it aside when he saw that it was bloodstained. On closer inspection he found the hillside was sprinkled with the blood of the Caco bandits, though no bodies remained.

“They carry off every body, and every wounded man,” Lyautey said. “And when they catch our wounded … well, Captain, if you see one, you will never forget. The Cacos believe that every man who dies must go before the gods—and they use their knives to see that when our men go, they are beyond recognition. They slash the face to ribbons, and tear the body apart. You will see.”

Puller was learning valuable lessons from the Haitian, and made it a point to be near him when the patrol halted for a rest. Every day or two, a soldier was detailed to shave Lyautey’s head, scraping the hair to the gleaming skull, and even at these times the big man tutored Puller:

“Captain, it is a matter of life or death for officers and noncommissioned officers to have respect from the men—and something more. Adulation. They must obey orders to the letter, without question, though they die for it. It is the only way to handle men in combat. If you lose control, you lose lives. It is so simple as that.”

About three weeks later, when he was off patrol, Puller attended the christening of the child born on the trail, and stood as his godfather. He was surprised to hear the priest call the name: “Leftenant Puller François.” It was the first of scores of namesakes in his long career. Lewis gave the priest five dollars and asked that a candle be burned for the child. “It will be done, Captain, and candles will be burned for you, and prayers said. Bless you, sir.”

A priest in this place told Puller of one Dominique Georges, a bloodthirsty Caco leader who had wrought much damage in the region and was now in camp about fifteen miles away. Puller told Brunot to pass the word that they would leave the next morning, and to see that it got public attention.

On patrol, Puller saw a few huts and many lean-tos, with several fires still burning before them. A burly man rose from a hammock in the largest of the huts, where there was a light, and shouted: “Who passes?” The sentry by the trail called reassurance: “Cacos.” Puller, Cermontoute and Brunot lay flat in the grass, and Puller held the big man in his rifle sights until he turned back to his hammock—he later regretted that he did not fire, for this was the bandit leader, Georges.

Early in 1920 after only eight months of combat experience, Lewis Puller was promoted to command the subdistrict of Port-à-Piment in a remote corner of southern Haiti. He was almost constantly on patrol. In April he was felled by malaria.

He was so weak one morning, with a throbbing head and aching body, that he could not leave his bed. He took large doses of quinine, and on the advice of his first sergeant tried rum as often as he could stomach it. In the fifth day of his fever he lost consciousness.

Lewis opened his eyes to see a stranger leaning over him, a Negro doctor. He turned and saw the round, benign face of the French priest who was the only other white man in the subdistrict.

“You have a bad fever,” the priest said, “but you will be better now.”

“I have given you quinine intravenously,” the doctor said, “and now I must give you more.” He held a huge hypodermic.

“My God! You must be a veterinarian.”

“The malaria does not easily surrender. You need have no fear. I am trained in France for many years. You will be better now.”

Puller walked the following day, and within a week was back at his duties. His first sergeant brought him a bill for two gallons of rum used in the cure.

He wrote friend Tom Pullen, back in the States:

You may rest assured I was relieved when I found that I had been ordered in to Port-au-Prince to be decorated for killing Cacos, and not to be court-martialed for the same. It’s funny as hell to me; every once in a while some misguided fool up in the States, who knows nothing of the trouble here, sets up a howl over a few black bandits being knocked off. You don’t want to come down here, Pullen. Stay in the States and make something of yourself. It’s a dog’s life here.… Unless I get into the Marine Corps, I have a pretty rotten-looking future ahead of me.

The next month, May, 1920, the Caco campaign came to an end with the slaying of the two chieftains, Charlemagne Peralta and Benoit Baterville, by patrols led by Captains Herman Hanneken and Cy Perkins. An armistice was declared and the tribesmen poured into the cities by the hundreds to give up their arms and make peace. Every soldier who brought in his weapon was given new clothing and ten dollars.

Puller was in Mirebalais in these days, intent upon studying the enemy. He talked with literally hundreds of the bandits, hearing their versions of combats in which he had fought—and searching always for word of the killing of his friend, Lawrence Muth, who had been the victim of a Caco ambush in the last week of the fighting. He had written Tom Pullen of the reports of Muth’s death:

In the fight with the Cacos a few weeks back Muth got his. The Marines and Gendarmes left him when they retreated. I surely hope he was dead when the men got to him. The next day, a large force hiked over to the scene. There wasn’t a piece of flesh or bone as large as my hand. His head is stuck up on the end of a pole somewhere now, out in the hills.…

Puller picked up Muth’s trail from a minor Caco chief, one Charlieuse, who was in the crowded town. Puller talked with him in his improved Creole, and the arrogant native warrior told of Muth’s end without reservation:

“They walked into our trap, and it was beautiful. Your Leftenant Muth, he was the first. He fell, but he was not dead, and when we drove the enemy away, we made talk with our gods.

“We were four chiefs, to make the sacrifice. As always, we took off the head from the Leftenant, and cut up his body.”

Puller sickened as Charlieuse told of the obscene atrocities committed on Muth’s corpse.

“Then we opened the chest,” Charlieuse said, “and took out the heart. It was very large. And we ate of it, each of the four chiefs, to partake of the courage of your Leftenant Muth. It was a glorious day.”

Puller controlled himself, and on orders from the commander took Charlieuse to the prison. Shortly afterward, however, the chief was killed in an attempt to escape his guards.

Lewis soon got a new post, as commander of the district of St. Marc, where he was military governor of a territory of hundreds of square miles of rugged country, with authority over courts, police and civil affairs for 105,000 people. He had never been so busy, for he was endlessly besieged by the problems of those who came to the little town.

He was ordered to build barracks for his outposts, though he had no experience and almost no money for the purpose. Headquarters sent just enough cement for the floors and sheet iron for roofs—the rest was up to the commander. Puller responded with vigor, and for months he drove trains of prisoners through the jungle in a style that reminded him of the building of the pyramids.

“I may go to hell for this,” he told a visiting officer, “but I’ve got to finish, like it or not.”

The Captain directed each outpost to raise vegetables and supplement the daily ration of ten cents per man, and somehow, despite handicaps, his little military empire prospered.

It was not until years later that Puller realized the full richness of his Haitian experience, and the value of its lessons in soldiering and hand-to-hand combat—he had fought forty actions. He had not only been blooded; the guerrilla combat had been almost continuous, most of it introduced by ambush on the trail. Puller had stood up well under this strain, and had come to trust his own physical prowess and ability to lead men under fire. He had discovered that native troops could become superb soldiers. He had developed his instinctive talent for using terrain in battle, and learned the lessons of jungle fighting. He had become strongly prejudiced against barracks and headquarters soldiers. Despite his youth, he was one of the most seasoned combat officers in the Corps.

Video Extras

Below, a video of John Wayne’s tribute to Chesty Puller, from 1976 by director John Ford.

Below, Puller, as portrayed in the HBO series The Pacific, from 1990