SINGAPORE – If a body politic is looking at how to move a struggling city from poverty to riches in a short time, Singapore is the model. When Singapore was founded after independence from Britain in 1965, it was not only poor, but it was torn by ethnic divisions from its un-formed national identity, including a departing British colonial mercantile and trading class, a Chinese majority, Indians and Indonesians.

Singapore had nothing of note in 1965, when it split off from the newly formed (and also struggling more) Malaysia. Neighboring Indonesia was against the formation of the country, and Singapore’s survival was tenuous. It had no national resources, no extensive education system, no industry, no social services, no defense, no land, no oil, no nothing. Just a year earlier, the tiny city state had survived Muslim race riots. What a way to begin a nation.

What Singapore did have was a port, about two hungry million people, and a leader named Lee, Lee Kuan Yew, who believed in the place. It also had a a statue of a British colonial, Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, situated in a prominent place for all to see.

Socialists & Colonialists

Singapore was also socialist, and very much along with the times, with Lee the leader of the People’s Action Party. However, Lee was a practical man; he knew that if he was to attract and keep investment from the west, he needed to not only signal to them that ethnic strife was not the dominant theme in the new country, but demonstrate that by his actions. Would that Mugabe had understood this lesson.

When many non-Western countries became independent from Britain, the first thing they did was tear down the statues of the colonials, and change the names of the streets and the cities. Lee wanted nothing of the sort for Singapore. His biography, from Third World to First, is the story of what he accomplished. I would commend it to any person who really cares about what happens in an inner city; the ideas and perspective are still useful.

One of the early actions of Lee was bold and brash, and cost him nothing. The action was to leave some things status quo, including the statue of Stamford Raffles, who founded the city. This idea came from a Dutch economist named Albert Winsemius, who was brought to Singapore in 1961 by the United Nations. It was one of Winsemius’ only two suggestions for Singapore’s success; the other was to root out the communists. Lee puts it better than I can:

To keep Raffles statue was easy. My collegues and I had no desire to rewrite the past and perpetuate ourselves by renaming streets or buildings or putting our faces on postage stamps or currency notes. Winsemius said we would need large-scale technical, managerial, entrepreneurial, and marketing knowhow from America and Europe. Investors wanted to see what a new socialist government in Singapore was doing to do to the statue of Raffles. … I had not looked at it that way, but was quite happy to leave this monument because he was the founder of modern Singapore. If Raffles had not come here in 1819 to establish a trading post, my great grandfather would not have immigrated to Singapore from Daup county in Guangdong province, southeast China.

Today, we all know the riches of Singapore. While it is not a perfect place, it has improved the lives of millions, and created a center of education, health and prosperity, and is a lesson to the struggling areas of the United States that are now poorer than what was considered a third world country. While some believe it to be a bit of a nanny state, it is a beacon of safety and free-thinking in Asia.

Confederate Preservation and Urban Removal

Around the South, there is a fierce discussion of whether or not to remove or move Confederate statues and monuments. The argument about it has been discussed on the wrong terms; once it gets to the point of latter day Confederate groups and Klans vs. politically correct activists, the statues almost always lose.

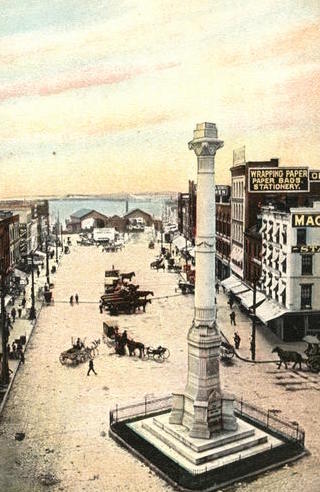

This is not what happened in Norfolk, where the Confederate Soldiers and Sailors Monument sits in the middle of Commercial Place. Most don’t even know or care what the monument is; it is up very high and meaningless to most. You can hardly see it; it looks like a pole with a man on top. Norfolk’s vice mayor put it well in 2015. Quoted in the Virginian Pilot, Vice Mayor Angelia Williams Graves said, “You can’t erase history just because you don’t like it. It is what it is. To remove it would be a mistake.”

Norfolk, my birthplace, is an enormously practical place, and quite diverse. The ironic thing about the monument in Norfolk is that it was just about the only thing historic that survived a massive “Great Societies” demolition binge that displaced thousands of blacks across the city and put them in public housing. The handsome 19th century commercial buildings in the picture here were replaced by modern banks that were used by whites, who then took a freeway away from downtown to live in the suburbs. The freeway also destroyed thousands of houses and businesses.

Meanings change over time. To me, the monument has little to do with Confederates, and instead reminds me each time I see it of the social and cultural tragedy that was “urban renewal” which really meant African American removal. If the true story and history is known, future generations can look to the Confederate to see true evidence of how prior generations of white leadership behaved.

The lesson? Whites did not look after black history, but blacks did protect white history.

Next Steps

The solution is not to take down what some don’t like, but to add new things that tell the story more inclusively. The victory in Singapore was that locals, after colonialism, made the place greater than it was under the British.

Richmond, happily, tenuously, seems not to be willing to take down its Confederate statues (they are part of city Old and Historic Districts, and contributing structures to neighborhoods on the National Register of Historic Places). Instead, in the 1990s the city constructed a statue for Arthur Ashe on Monument Avenue, and just this month dedicated a statue to black entrepreneur Maggie Walker. A statue of Lincoln and son Tad also went up in Richmond in 2003. In this scenario, the inclusive and diverse cultural narrative wins by adding to and superseding, rather than taking away.

In some cities like Charlottesville and New Orleans, elites have not been supporting the preservation of these monuments as they should, and they have left it up to Confederate history groups and supposed Klan members to defend them. This is disaster for everyone. Sadly in 2003, Sons of Confederate Veterans protested the Lincoln statue in Richmond, on National Park Service property even, and they did themselves no favors.

Preservation groups, art museums and cultural elites are often afraid of conflict, and can be politically correct to a fault. I witnessed this in Richmond in 1991, when I saw an ante-bellum 1840s house illegally demolished across from my companion Greek Revival house; the historic preservation professionals were afraid to speak out as the demolition was by an African American church that needed parking.

What was needed was an honest conversation about the real problems, and by the time of the demolition it was too late to provide that conversation.

One idea of historic preservation in the last few decades is that preservation is not about preserving an idealized past, or a prettified past. We preserve things for a number of reasons. The structures might be visually good and satisfying. They might they tell a forgotten story, not just because a certain famous person walked there. They might be just plain unique, or beloved, or idiosyncratic. Or they might just be plain useful; ergo a plain steel warehouse redone for apartments.

Future Preservation

The effort to remove Confederate statues will not end with Confederate statues; it will move to any sort of edifice that is deemed offensive. The scars on the landscape will remain, and the replacements will never be as good as the originals. The Klan types will be even more angry. Whatever you think of Lee, the statue of him, and Traveler, is a masterpiece by Antonin Mercie, who has only two other statues in the U.S. (Francis Scott Key and Lafayette) and is mostly known for his work at the Louvre in Paris. Yes, the Louvre. That Louvre.

Certainly in the heat of a battle or revolution, certain monuments can be destroyed; dime a dozen Stalin statues were pulled down in Eastern European countries in the height of transition of power. However, in recent times countries have left these monuments up. Not because we love Stalin and his pogroms, but because we need to get on with our lives, and some of the statues are beautifully done, even as they tell a story of the time. They also fill a hole in marking a civic place.

Perhaps the situation with Confederate statues is partly analogous to the Volkswagen, another beautiful piece of sculpture associated with a nasty piece of history. Here was a product, created by Nazis at the height of their evil, and to any an average person even today, the Volkswagen is known as Hitler’s people’s car. Yet Americans helped restart the factory after World War II. The reason? Not only did Germany need to get on with its life after the war, but the car was an enormously useful and beautiful thing. Statues do have a utility; they shape our public spaces.

Certainly, I know of some who served in World War II who might not drive a Volkswagen. I know of some vets who also will not EVER buy a Krups coffee maker, such is the stigma. But they also recognized that others did not have to share that emotional burden.

Whether a church removes a Confederate stained glass, or a city moves a monument to a cemetery, or renames a street that was named after Jefferson Davis, the reality remains that there was a Civil War, and it was painful for all sides. The problem with removal is that when the item is gone, the story behind it gets forgotten. The only story that remains is the story of the removers. There is a bit of cycling around in history; what you do can very often come back to the group that did it, turning civic engagement into a sort of Kosovo.

If all the Confederate statues are sent to museums and graveyards, the misery of the aftermath of the Civil War will still be there, and the people who removed them will still be aggrieved and they still suffer from the ills of modern American culture. But the markers of how we got there will be gone, and a future generation will be able to live without the knowledge of what happened. That is not a good place for a culture to be.