When locals are negative about the economic future of their own towns, watch out.

When locals are negative about the economic future of their own towns, watch out.

The negative stories and “memes” that are told over and over again take on the veneer of truth, and then begin to affect the psyche of the city. Such stories as:

- There is little hope for this XYZ town.

- All the young kids are moving away from XYZ county.

- Since the XYZ Factory closed, there is no opportunity.

Of course, the reality is that factories do close, governments are corrupt, and corporations are very often so focused on the bottom line that they are happy to run a company into ruin, and tear the heart out of a city. And people do have to leave when there is no opportunity.

But that’s different than a town’s own mantra, which usually comes from some in the the ruling class that had a stake in creating the old, unsuccessful order.

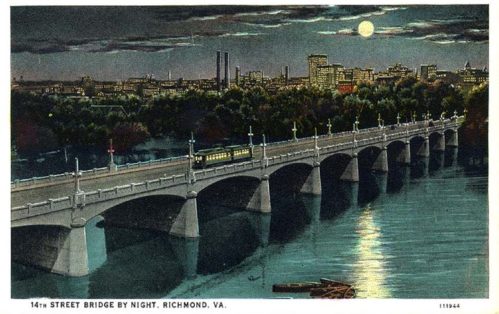

This was certainly the case of some in Richmond, Virginia, which had a persistently negative view of itself, in spite of its riches in architecture, culture and people. Pictured here, a lovely painted postcard of the 14th Street Bridge, with a lighted trolley going across at night. A delightful place.

All during the 1980s, when great Virginia banks like Virginia National Bank, State Planters Bank and Central National Bank were being sold out by elites into stupid-named banks like Crestar, Signet and Sovran, and then sold out again to newly created national banks, one of the many negative Richmond mantras went something like this:

- Virginia, unlike North Carolina, deregulated its banks late to allow state-wide banks. Because Virginia was so behind, North Carolina banks got more powerful, and that’s why we had to sell out to the likes of NCNB, Wachovia and First Union. That’s why North Carolina won all of that and we are so miserable.

Of course, I made that last sentence up completely. It’s a sort of paraphrase.

Of course, there was some truth in it. Richmond was slower to deregulate its state banks and allow consolidation. But further questions were never asked including was the deregulation the right idea in the first place? What can we do to preserve bank jobs? What banking related industries can we attract to rebuild lost white collar jobs?

And there are were other memes. Richmond is so racist, northern companies don’t want to be here. The Club won’t let in all the relocated employees, and so they feel left out. City government is so corrupt they are scared to open a factory here. On and on.

Today, things have come full circle, in spite of the negative meme. A few years ago, Forbes listed the “Cities that are Winning the Battle for Finance Jobs:” And what was the city with the most growth? Richmond, Virginia with a total of 47,000 people who worked in the financial sector. In the stats, Richmond gained 12 percent in finance jobs from 2009 to 2012, a 12 percent gain overall and 4 percent gain in 2012.

Much of this is because of the success of Capital One, which was born as Bank of Virginia Charge Plan, and spun off. Of all the charge cards, Capital One has a gentler approach; I worked there for a time and it was a fantastic company. It was growing, both in Richmond and in Northern Virginia, its headquarters. So much was the growth a few years ago that they had to have a shuttle bus from their Richmond campus to Northern Virginia. But it wasn’t just Capital One, but smaller brokerages and banks, as well as insurance and other finance and accounting. Small boutique investment banks also opened up.

Another factor has been the presence of the Federal Reserve, federal courts and state offices. This legal and financial infrastructure helped carry prestige of the the financial sector when many of those banks sold out.

Through it all, Richmond had steady leadership in their regional economic development personnel, including the longtime head of the Greater Richmond Partnership, Greg Wingfield. Wingfield was consistent in his positive message, and focused carefully on recruiting in industry clusters, using asset-based methods.

Go to any city that is ailing, and ask what is wrong. You will get an “answer” that might be technically correct for a time, but it does not explain why the city fails in the long term.

For a time in Richmond, I worked in Petersburg at their afternoon newspaper The Progress-Index. I loved the paper, and the city was gorgeous, with almost as much historic architecture as Richmond. But it had been hit hard by the closure of Brown & Williamson’s tobacco operations. The once-famous home of Raleigh, Kool, Viceroy and Kent became a scary place in some areas, even as there were successes in the restoration of Old Town Petersburg. A small group of devoted people kept looking forward to preserve old buildings and history, but the whole place became negative about itself, and all the middle class whites and blacks had to leave because the schools were awful. It was not good, and in some ways I felt that Petersburg was sort of cursed with a type of demon. I hope things are better now.

Part of the revival of Richmond has been in architecture and urbanism; many of the elites in Richmond made a commitment to preserving the history and architecture of their city. I remember one Virginia visit of urban planner Andres Duany back in the 1980s; I wish I had the year. As a reporter, I went to ask him about some of the problems of Richmond, of how the city was ignoring its urban fabric. Duany did not disagree. But he then put the onus back on me. “Tell me what is right,” Duany said, wanting to hear examples of successful urbanism that one could build on, to fix the bad areas.

Tell me what is right.

That’s a lesson that goes well for cities, and it works well in life too.